Color-blind racism is the result of systemically using nonracial dynamics to explain racial matters. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva breaks this concept down into four distinct subcategories that ultimately perpetuate the continued racial disparities that have plagued this country since its inception. This form of racism is subtle and more difficult to identify due to the lack of obvious malice in tone or intent. This ideology rests on the basis of, “abstract liberalism (explaining racial matters in an abstract, decontextualized manner), naturalization (naturalizing racialized outcomes such as neighborhood segregation), cultural racism (attributing racial differences to cultural practices), and minimization of racism.” (Bonilla-Silva, 2022, p 343). Regardless of the delivery method employed, color-blind racism limits our understanding of the structural nature of the racial problems revealed during the Covid-19 pandemic by ignoring the systemic root causes of racial disparities and focusing too narrowly on individual causality to explain it away.

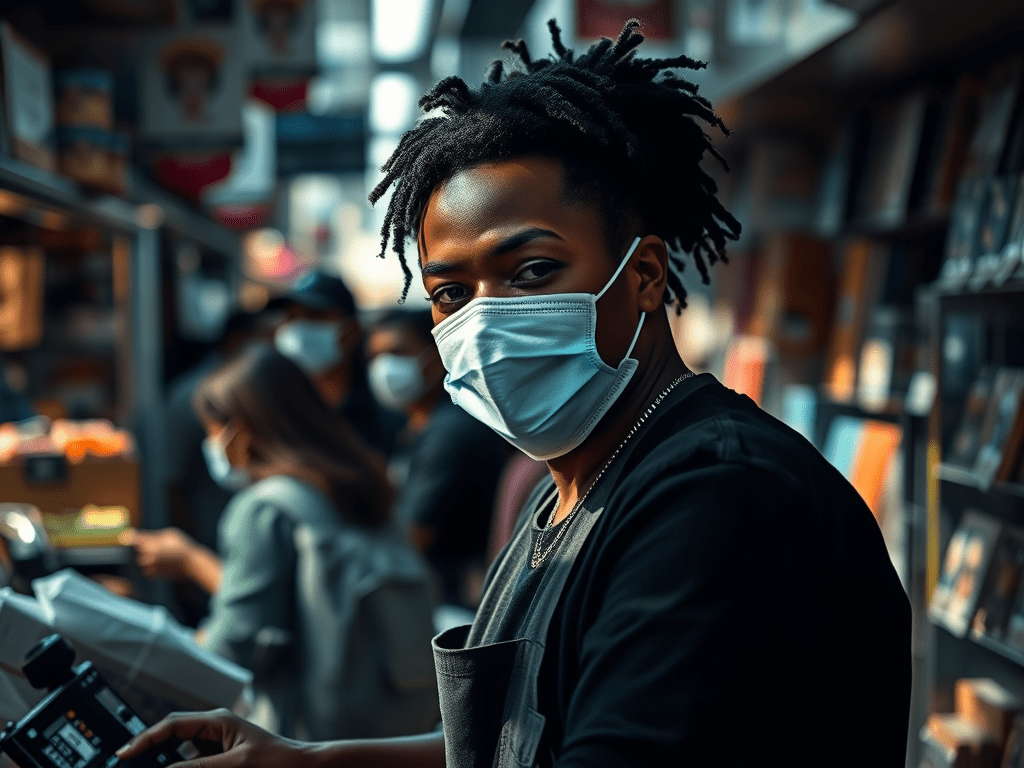

Abstract liberalism expressed through phrases such as, “we’re in this together,” and “frontline heroes,” Ignores the overrepresentation of people of color in industries with higher levels of exposure to the virus, and stops us from asking why they are overrepresented in the first place, or why such “essential” jobs pay so little that the choice to stay home and stay safe with their families was never an option if they didn’t want their family to go hungry. Hunger is often addressed in society through channels of charity rather than addressing the governmental policies, corporate business practices, or the symbiotic relationship between the two that lay the foundation for hunger as a systemic social problem. As Bonilla-Silva pointed out, “Framing hunger as a charity matter derails us from thinking about why workers were out of food after just a few weeks of unemployment, why there were such high levels of food insecurity before the pandemic, and, more significantly… the fact that hunger is also a highly racialized affair” (Bonilla-Silva, 2022, p.346). During a CNN special on covid, Charles Barkley demonstrated naturalization when he acknowledged systematic racism as a contributor to the disproportionate effect Covid had on the Black community, yet immediately followed it up by calling on individual members of the Black community to improve their own individual health concerns without acknowledging how racially segregated BIPOC[1] communities are prone to have less access to healthy food, adequate healthcare, or safe spaces for physical activities, nor the additional burdens of higher exposure to pollution, inadequate or unsafe housing, or the interpersonal discrimination they face. Barkley demonstrated that due to the systemic nature of racial disparities in America, even individuals from the BIPOC community attempting to make a difference can perpetuate racial inequality unintentionally through naturalization. Even when social predispositions are acknowledged, color-blind racism persists due to culturalization. For instance, when Surgeon General Adams addressed that while there are social causes to the disproportionate mortality rates of Covid among the Black community, there are also physical diseases that disproportionately make them more vulnerable, he did so without addressing the social factors that contribute to that disproportionality. This indirectly associates the disparity as a “Black” issue rather than addressing the structural nature of the problem, and ultimately minimizing the role of racism.

Barkley and Adams demonstrate that intent is not necessarily a factor in the persistence of the structural elements that perpetuate racial disparities within and throughout society. While color-blind racism may be a component of the structural nature of racism, its foundation is rooted in the institutions of which this country was built upon. Bonilla-Silva purports that not only is the issue not due to individual choice, but it was also not a naturally occurring process either. Instead, he addresses the issue as, “the product of racialized practices of banks, realtors, individual Whites, and the government” (Bonilla-Silva, 2022, p.348).

While science and medicine have in the past been responsible for perpetuating the racism that it so engrained in our society, Bonilla-Silva suggests not that we shy away from those avenues in search of a solution, but rather to engage them in public discourse so that we can address the impact power relations of race, class, and gender, as well as the imperialistic birth of our nation, has had on our scientific and technological institutions, and together work towards an equitable solution. To truly escape the societal issues that come with our racist national origins, we must remove its presence from the entire infrastructure of society, rebuild entire institutions, such as policing, and rebuild them with an equitable framework. Segregation and immigration policy reform, as well as increased access to free healthcare would greatly impact racial stratification in America. Bonilla-Silva reported that, “experts on health disparities have urged immediate interventions such as providing hazard pay to workers, reopening the Obamacare exchange, dropping Medicaid work requirements, and reversing plans to allow Medicaid spending caps to reduce the mortality gap” (Bonilla-Silva, 2022, p.348).

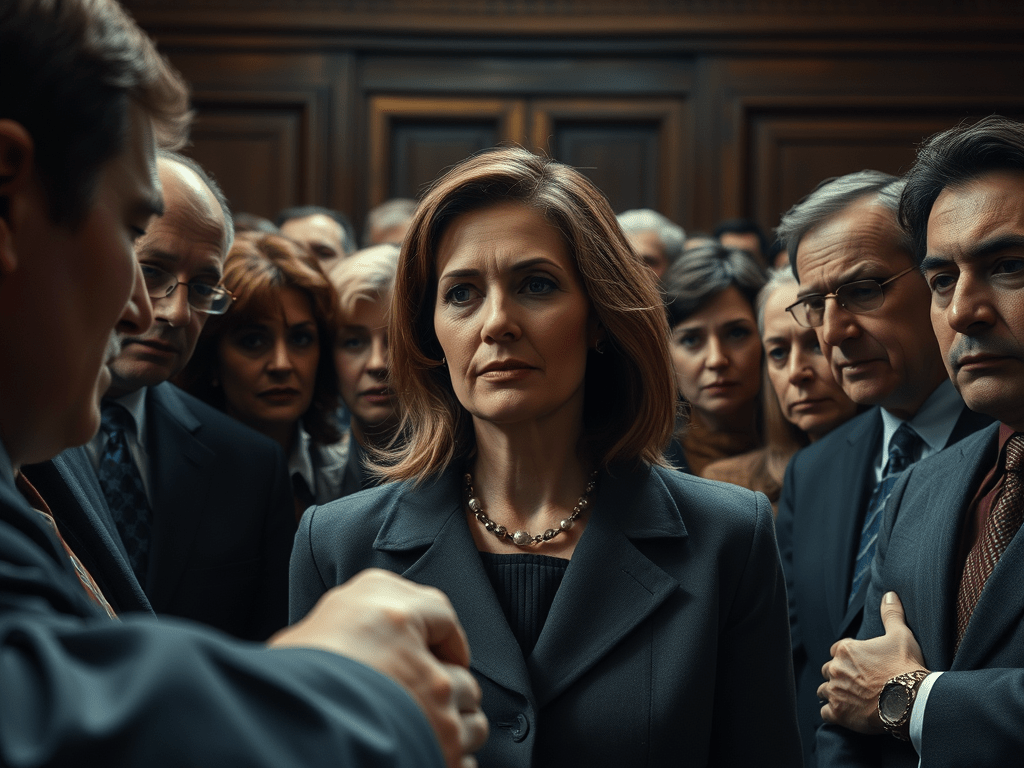

While facing structural racism, especially for the white community who unintentionally support or perpetuate its prevalence, may be a difficult and uncomfortable task, it is a necessary step in identifying and eliminating the tools of color-blind racism that grease the wheels of the systemic machine of structural racism engrained in our society. We must be able to have uncomfortable conversations, call out instances of color-blind racism (or any racism), and no longer provide a safe space for racial tropes, stereotypes, or insinuations for the sake of “keeping the peace,” or the vanity of avoiding uncomfortable conversations. Continued social protest and other forms of pressure against the systems that perpetuate racism and the subsequent societal ramifications that accompany them is crucial in addressing this issue that is as old as the nation itself. While the race rebellion of the 1960’s knocked on the door to racial equity, our generation must burn it down so the powerful minority can no longer slam it shut on the powerless majority before true progress can be achieved.

Intersectionality

While racism truly is at the core of inequality in America, there are many segments of society that have been historically stratified from opportunity. Most people who experience social or economic stratification do so because of a variety of often overlapping and interconnected reasons. Intersectionality is an approach that addresses the multidimensional factors that contribute to inequality (Crenshaw & Harris, 2008). For example, a Black, female, lesbian with a physical disability would be faced with social challenges in four separate areas of marginalization. By applying the concept of intersectionality, we can seek to understand how not addressing complex identities causes discrimination and social stratification to affect individuals in a variety of ways and hinder the progress of social movements.

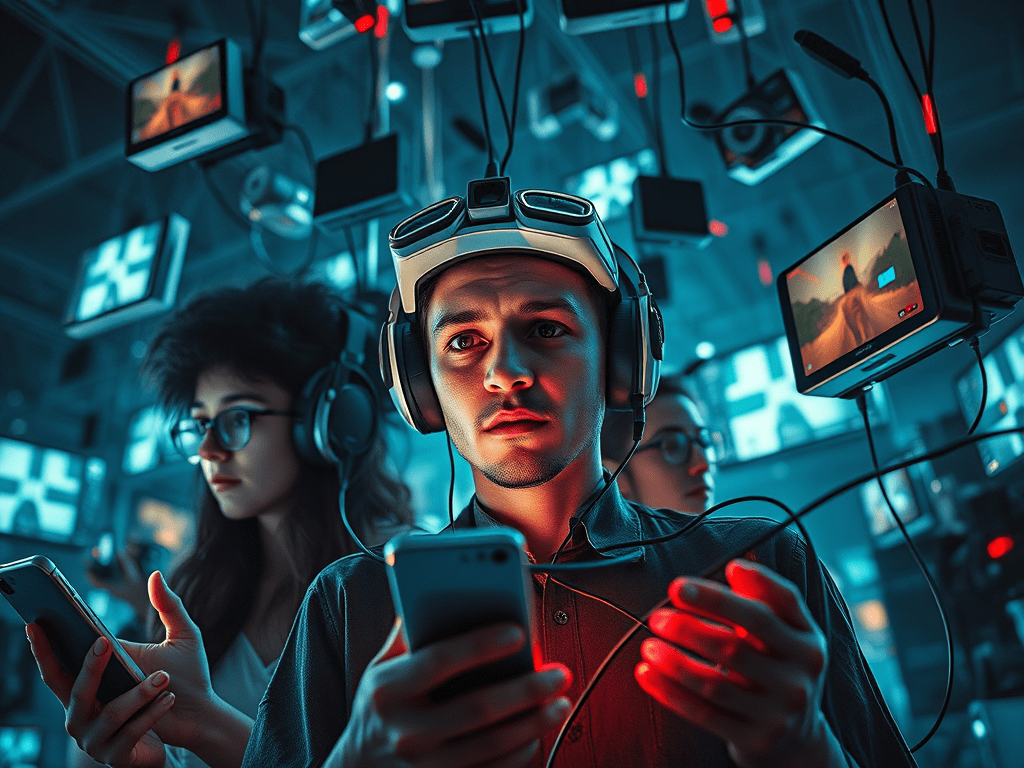

The single-access approach to solving social problems is different from the Intersectional approach in that it addresses different social problems such as race, class, and gender, separately and exclusively. This method is often ineffective, and according to Crenshaw and Harris, “even lead to unnecessary exclusion and conflict within social justice movements” (Crenshaw & Harris, 2008, p.2). The benefit to viewing marginalization through intersectionality is threefold; it allows us to analyze social problems more completely, create more effective policy interventions, and promote more inclusive advocacy (Crenshaw & Harris, 2008). In contrast, the single-access approach can exclude or disadvantage members of society that exist within multiple subgroups through bad policy and conflict within social justice movements. Intersectionality provides a better prism to understand social justice issues than the single-axis analysis because it provides a perspective that Crenshaw says allows us to, “view a range of social problems to better ensure inclusiveness of remedies, and to identify opportunities for greater collaboration between and across social movements.” (Crenshaw & Harris, 2008, p.3).

Bonilla-Silva’s ideas surrounding color-blind racism provides one example of why an intersectional approach is better equipped for solving social problems than the single-access approach. He addresses the severe racial disparities exposed during the pandemic, and the multidimensional nature of societal marginalization that perpetuates them. Intersectionality addresses the issue of abstract liberalism by providing a framework that grounds the conversation in something more tangible for the individualist masses to conceptualize. Racism as well as all other forms of group stratification often go unnoticed by those unaffected by its presence. For example, it is difficult for a White person to understand the complexities surrounding the disproportionate policing of Black Americans because it is simply not a part of their experience. The concept of intersectionality zooms out, offering a perspective that may expose the White community to the ways in which these issues affect them too.

Framing the racial disparities exacerbated by the pandemic through the lens of colorblind racism seeks to address the issue by calling attention to the blind eye, missed connections, and misdirected understanding of the systemic nature of the problem, and by calling out the individuals and institutions that perpetuate it. An intersectional framework would allow more segments of society to see how they affect and also are affected by structural racism and other avenues of stratification. For example, in order to demonstrate how hunger is a racial equity issue, Bonilla-Silva highlights that despite a rise in food insecurity among all races, there are stark differences between Whites and Black and Latino groups. This gives the illusion that hunger is not a problem for White people. Rather than focusing on the fact that food insecurity is more prevalent in communities of color, an Intersectional approach would view the issue by highlighting how food insecurity has risen, and that it has affected all races. By not excluding the white demographic from the conversation simply because the issue is not as bad for them, you give them an opportunity to contemplate how the issue does or can have an impact on them as well. This perspective is rooted in a collaborative framework and promotes inclusion rather than alienation.

Works Cited:

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2020). Color-blind racism in pandemic times. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 8(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220941024

Crenshaw, K., & Harris, L. (2008). A Primer on Intersectionality – University of Alberta. A primer on Intersectionality. https://www.ualberta.ca/institute-intersectionality-studies/media-library/intersectionality-readings/a-primer-on-intersectionality.pdf

[1] BIPOC is a term used to describe Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. It’s use in Social Justice and Race issues is an attempt to highlight the disproportionate disparities Black and Indigenous communities experience, even among other ethnic minorities.

Leave a comment